- Home

- :

- All Communities

- :

- User Groups

- :

- Conservation GIS

- :

- Documents

- :

- On GIS, modesty & the problem of racial privilege

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

On GIS, modesty & the problem of racial privilege

On GIS, modesty & the problem of racial privilege

(part of the new Esri Conservation "Inclusive History of Conservation GIS" website project)

Like many commentators & historians I've listened to, I agree that 2020 will be an historic year, probably the most impactful in my 66 year life. Many of the reasons are bad ones, though some of the most important reasons are good ones, such the widest national protests ever and the beginning of important yet difficult national conversations and institutional changes.

One of these conversations is about racial privilege, an assumed set of comfort and safety features for a dominant culture that they never talk about, but that are obvious and problematic for other cultures. It's like getting on a plane where everyone is forced to stand there and memorize the entire safety card front to back before they can board, except privileged passengers, who enjoy the unspoken assumption that in the event of a water landing they'll be rescued first.

It's a difficult topic for privileged people to talk about, with plenty of negative shame labels like "guilt" or "snowflake" to keep the topic hidden. It's also difficult to survive and feel safe in my country if you are not privileged, that's what day after day of peaceful protests are trying to tell us. There is also an uncomfortable confusion between the idea of talking about one's "privileges" and boasting about oneself, something that people of good conscience try to avoid. This same confusion has come up in relation to my 31 years at Esri.

Esri has led the GIS world in innovation and a thriving user community for over 40 years. It has done this using a technical architecture first created and implemented by Scott Morehouse in the 1970's. To my knowledge, there is no other technical architecture or product line which has been an effective industry standard for so many years. Microsoft Word comes close, yet it's first release in 1990 was still 8 years after ArcINFO ver 1. But development genius is only part of the story. There are many development geniuses in tech, what made Esri unique was a different kind of corporate culture. The norm in tech culture is inspired leaders who express a vision for the future and work to motivate everyone to achieve that vision. I once heard Jack Dangermond say that this was a perfectly acceptable way to run a company, It just wasn't his way. What Jack told me next was what made Esri so different. Jack described his notion of what true leadership was: the higher you rise in an institution, and the more authority you have, the more you must recognize that that authority arises from all of the people around you, at all levels, and the more you must place their needs above yours, dedicate yourself to working for them, in their service, on their behalf. Jack's model is to be constantly building up the people around him so that they could be effective leaders. One aspect of this culture was the reluctance by Jack or other Esri leadership to give interviews or talk about themselves. This was more than simple modesty. It was a deeply held belief that the real GIS stories weren't about them, they were about all of these other people, especially Esri's users, and the hard work they all did, the obstacles they overcame. This tradition thrives even now as an important part of the annual conference plenary, where the story of GIS is told through a dozen or so slides of user stories. By comparison, In 31 years of user conferences I have yet to see even a single slide about Jack Dangermond or any of the other Esri leaders. Interviews began to be tolerated about 10 years ago in part because at a certain point, Esri's users themselves began to ask for them.

Jack's concept of leadership also affected my ideas about starting a new international nonprofit devoted to serving the conservation user community. In my case the decision was to never serve on the board of directors, but instead work within the committees, helping them to succeed and to help new leaders to emerge. This was a complex task even for the most selfless of workers, which I was not. My success in this "leading from underneath" has ranged from decent to at times awful. Still, the Society for Conservation GIS (SCGIS) has survived and grown for over 30 years, despite being 100% volunteer run. My greatest personal failure in all those years was my inability to include tribal & First Nations people in this Society. My initial proposals & charters talked equally about supporting First Nations communities with conservation groups. In my grant-making work at Esri it was no problem to make the first grants of GIS technology to many hundreds of tribal organizations in the 90's, helping them begin on the road to GIS capability. But I was never able to match that success when it came to the people and professionals who would want to be part of the Society. That was a lesson in racial privilege, hidden things about me that affected my relationships with communities of color, and that made it impossible for me to create a safe and welcoming societal environment for them.

As noble as the goals of modesty & leading from behind may be at first sight, they are also outwardly similar to the same silence that keeps racial privilege hidden. The motives are different to be sure, but the outward appearance is the same. I had much to learn about this.

The breakthrough began in 2018 when Janice Thompson, the head of GIS for Wilderness Society, began a new initiative within SCGIS called "Mapping for Advocacy". Wilderness Society is like the Sierra Club in it's commitment to diversity, so for Janice the word "Advocacy" was as much about social justice as it was about conservation. Together with Sandra Coveny, a GIS consultant specializing in tribal resilience planning, the SCGIS Tribal & First Nations program began that same year, with invited speakers from several US tribal organizations. I was honored to be part of that first panel. What I learned then was that there is a longstanding tradition among tribal & First Nations people that any gathering must begin with heartfelt introductions. These are not typical western introductions of name & employer or job. Instead, each person must tell who your ancestral people were, what landscape they are from and how you honor & represent them today. As was explained to me, before anyone can understand the words you are about to say, they need to first understand who you are as a human being. It was the first time I got to have a glimpse of what a world might look like where people of many cultures had empathy and understanding for one another. I get it now why this is such an important tradition for helping a gathering of people feel respected and heard, no matter what their origins and life experiences may have been. The fact that this cultural shift was finally beginning to happen in a Society devoted to the tools and practices of GIS made it all the more significant. In the same way that GIS was able to change natural history from a narrative tradition into a quantitative, predictive ecological science, my hope is that GIS can also help communities of every kind work together to identify bias and privilege wherever it exists and support one another in innovative & sustainable solutions. Towards that end, I hope to return with additional columns & essays in the coming weeks. First however, is my introduction as I was taught to do it:

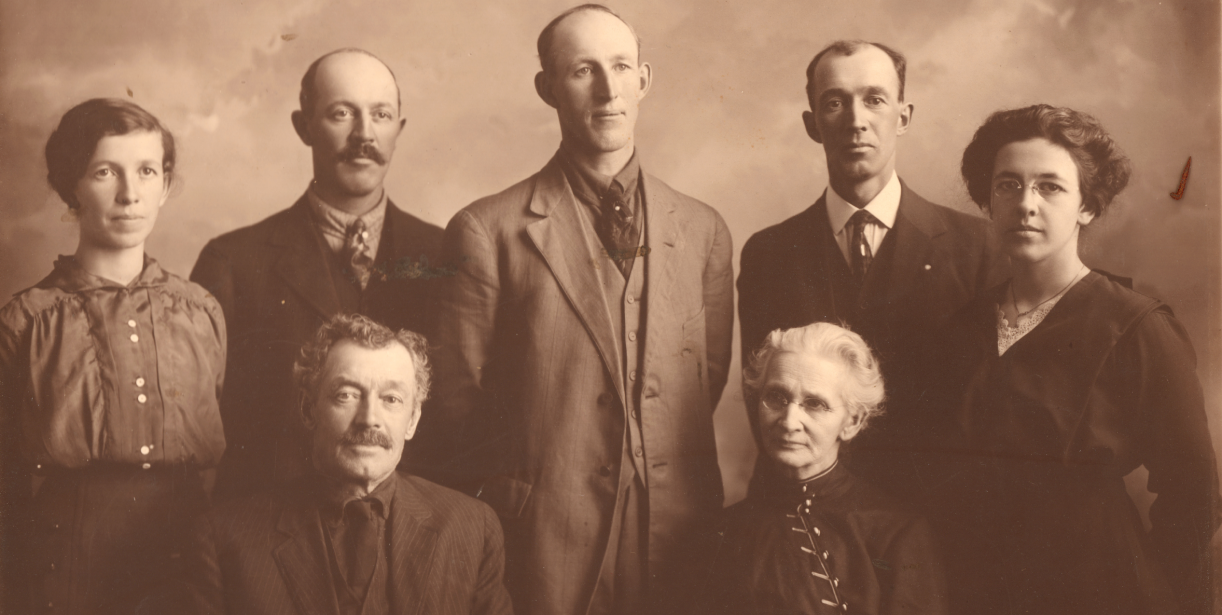

My name is Charles Convis. I am the 6th person of that name. I am responsible to my ancestors and I have studied my family genealogy since childhood. My ancestors were farmers, laborers & warriors in Europe until the late 1500's. Most of them came to America in the early 1600's, many were farmers and leaders in the Presbyterian church. Others were leaders against injustice, creating the first written American anti-slavery protest in 1688, and fighting alongside Black Marines in the Pacific in WWII. I honor their values and try to live up to their traditions of service and justice. I now live near the mountains called Nilengli near the place called Yukaipat by the Yuhaviatam (Serrano) people, who were the first stewards of what is also called the Inland Empire of California. My passion for conservation and my sense of self began as a child in another place, the High Sierra, first home of the Miwok & Yokuts. This always was and still is the landscape I am in when I dream, and the place of my stewardship. I am not neuro-typical, and this may be why I am better with machines and computers than I am with people. I am fond of GIS and believe it offers great hope for humanity. I am fond of photography, as it helps me to express my vision of how remarkable and beautiful are the many different people I see, even if I am afraid or unable to speak the words. I am cisgender and a member of my country's dominant culture. I am privileged by the society I live in, and I am just barely beginning to understand how to express myself in words that will make it safe for people different from me to hear what is in my heart and not what is in my skin.

(My deepest gratitude to my reviewers & advisors. Marsha Small (Tsistsistah (Northern Cheyenne)) advised against my many mentions of the words "white" and "black", saying that even naming skin colors reinforces colonialist divisions and barriers between people. Marsha also taught me how to properly introduce myself to others. Ashley Du, head of the Esri ECOS Environmental initiative, helped me with editing and introduced me to the concept "intersectional environmentalism". Sandra Coveny, tribal resilience consultant, encouraged the idea of an essay on this topic for conservation GIS readers.)

xconservationhistory

Thank you Charles! The philosophy you are sharing about Esri is really the reason why I joined the Esri education industry team. I had been observing the team and Esri for 15 years prior to joining it, so I had done my homework on it. Yes, we like the spatial data and the GIS tools, but our mission is really to do all that we can, wherever we can, and in as many disciplines as we can, to assist, support, promote, build up faculty, teachers, students, deans, provosts, after-school coordinators, librarians, and anyone involved with education to be successful with geospatial technology. It is all about helping them, not building up ourselves. The reason is to build spatial literacy for a more sustainable, healthier, happier world, that's really why we do what we do. And another of your points resonates with me as a geographer and educator--the longer I am in these fields, the more I realize I need others for assistance and support, whether technical or otherwise.

--Joseph Kerski

Thank you Charles.

The internal compass is always the most important bearing to calibrate in life--so we can lead by example and follow with purpose.

My career in GIS has been blessed by the privilege I was born with, that which has been shared with me and that I can share with others.

You have shared much and your leadership has showed me how to share that with others.

I grew up between Folsom and Donner Pass in the watersheds shared by Nisenan people and owe much of my success to the lives of my immigrant ancestors who came to settle at Sutter's Fort and to work for the Stanford's.

I owe much to that wonderful landscape that taught me by being in it and what was and reinforced by what I learned from Maidu people and living near Maidu Regional Park.

I also owe much to how I am by what repelled me about the destruction of landscape and people as I played in the mountains of rock tailings from hydraulic mining along the banks of the river between the duck and cover drills (common for kids surrounded by 3 air force bases and missile manufacturers during the Cold War).

In my career in environmental education between 1985 and 2004 it became clear that geographic literacy was the most essential gap I encountered whenever teaching.

Biology that informed conservation action or environmental justice requires sense of place, orienteering, and the relationship of biology and geography to them.

When I added GIS to my education work and transitioned to a career in GIS between 1999 and 2004, you and Charlie Fitzpatrick were there saying and doing the things I saw as so important, the same important things shared by the people where I grew up.

GIS and ESRI tools were part of how you broadcast all that good knowledge.

This strengthened my resolve that my work could be do that too.

I look forward to running into you again and for your next introduction as you bring daylight to your strengths and flaws so you can purposefully evolve.

By then I hope to have more to add to my introduction due to the changes and growth brought by honing the skills of curiosity, compassion, serendipity, and giving.