- Home

- :

- All Communities

- :

- Industries

- :

- Education

- :

- Education Blog

- :

- GIS Graduates Want More Coding, App Building, IT

GIS Graduates Want More Coding, App Building, IT

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

Many educators are aware of the ongoing evolution of GIS from a desktop-centric, standalone software product to a web-centric platform that’s increasingly integrated with mainstream information technology. Not everyone knows what to do about it, however.

Educators often ask Esri’s education outreach team for advice about GIS curricula. To inform our advice, we asked members of Esri’s Young Professionals Network – most of whom are recent graduates – how well prepared they felt to compete for “good jobs involving geospatial technologies.” Their responses suggest a perceived gap between what graduates learned in higher education and what they feel they should have learned.

The Young Professionals Network is a diverse group of over 4,000 individuals. Membership is free and open to anyone. The sign-up form simply asks new members if they are “recent graduates,” but they are not required to be so. YPN-themed sessions at Esri events provide career and professional development advice, and opportunities to network with others in similar circumstances.

Twice in January 2017, we invited YPN members through their Facebook group to participate in our 10-question online survey. 226 did. We do not know if this sample is representative of the entire population of YPN members. For that matter, we don’t know if YPN members are representative of the broader population of job-seeking graduates of GIS-focused higher education programs. However, we can reasonably assume that respondents cared enough about the survey’s topic and goals that they made time to respond. Thus, we’re confident that this reasonably large sample of motivated respondents provides useful information.

Although YPN membership is open to anyone, GIS users are most likely to opt-in. Three quarters of our survey respondents indicated that their “full-time job involves geospatial technologies,”, while 17% more said they were “looking for a job that involves geospatial technologies.” Of those who were working in the field, 45% said it was “somewhat difficult” or “difficult” to find a “good job.” Only 39% said the process was “somewhat easy” or “easy.” The rest are still looking.

Responses to the survey question “Name the discipline in which you earned your degree.”

Respondents named 36 different disciplines in which they earned their highest academic degree (mostly bachelors or masters degrees). Geography was the most frequently cited discipline, but only by 28% of respondents. Other frequently cited disciplines were Environmental Science, Policy or Management, Geographic Information Systems or Science, Geomatics, Geoinformatics or Geospatial Engineering, and Urban, City and Regional Management or Planning. The variety of academic backgrounds that current and aspiring geospatial professionals bring to the field is remarkable. Three quarters of respondents were “recent graduates,” which we defined as individuals who earned their highest degrees within 5 years or less.

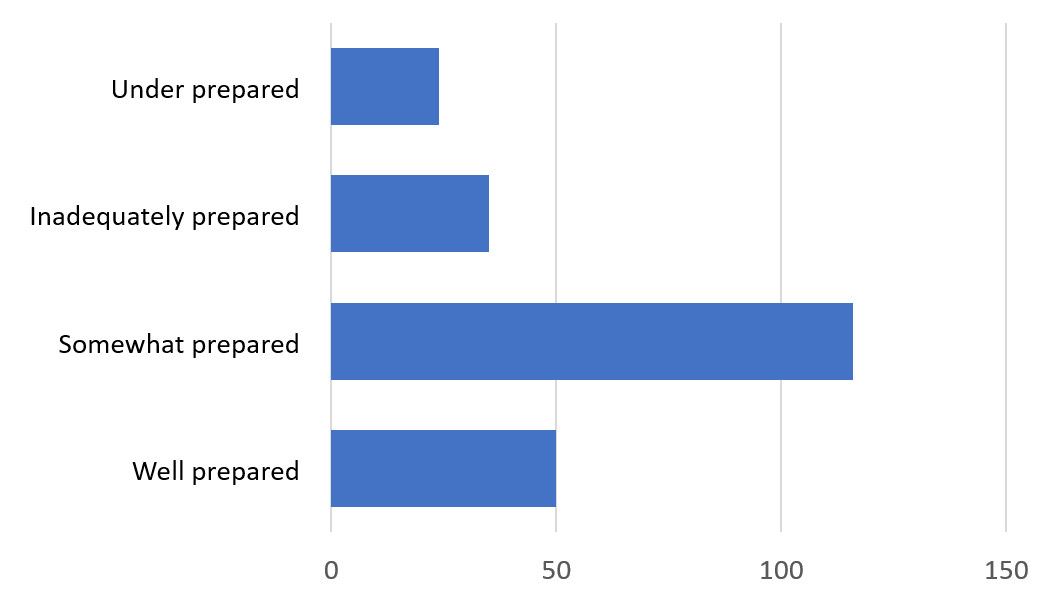

Responses to the survey question “When you entered the job market, how prepared did you feel to compete for a good job involving geospatial technologies?”

Slightly over half of respondents said they felt “somewhat prepared” to compete for a good job involving geospatial technologies when the entered the job market. More than a quarter felt “inadequately prepared” or “under prepared.” Only 22% of respondents felt they were “well prepared.” Is that good enough? Do graduates feel better prepared in some areas than others?

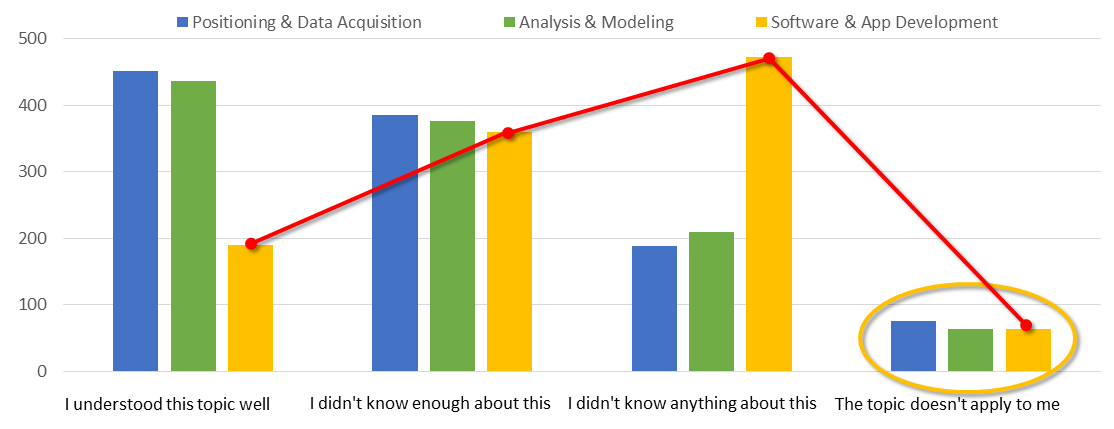

The heart of the survey was three questions in which we asked YPNs to assess themselves against competencies specified in the Department of Labor’s Geospatial Technology Competency Model. For each of the three Industry Sectors – Positioning and Data Acquisition, Analysis and Modeling, and Software and App development – we asked respondents to rate themselves on five competencies. For each competency, respondents could choose “This topic doesn’t apply to me,” or “I didn’t know anything about this,” or “I didn’t know enough about this,” or “I understood this topic well.”

Questions 7, 8 and 9 asked YPNs to “Rate your knowledge and abilities at the time you earned your highest degree

in relation to [the three sectors of] Tier 5: Industry Sector Technical Competencies, U.S. Department of Labor Geospatial Technology Competency Model.”

The four answer choices were associated with ordinal-level ranks, 1-4. For analysis, we summed all responses for each of the three Industry Sectors. The sums are depicted in the following graph as colored bars, where blue represents the Positioning and Data Acquisition sector, green is Analysis and Modeling, and Software and App Development is light orange.

Responses to questions 7, 8 and 9, “Rate your knowledge and abilities at the time you earned your highest degree

in relation to [the three sectors of] Tier 5: Industry Sector Technical Competencies, U.S. Department of Labor Geospatial Technology Competency Model.”

The first thing to note about these three distributions is that very few respondents indicated that any of the three sectors “doesn’t apply to me.” Ninety-four percent or more felt that competencies related to positioning and data acquisition, analysis and modeling, and software and app development are all relevant to their careers.

The second thing to note is that the distribution of responses is very similar for the first two sectors, Positioning and Data Acquisition and Analysis and Modeling. However, the distribution of competency ratings for Software and App Development is markedly different. Many fewer respondents stated that they “understood [those] topics well,” and many more said they “didn’t know anything about” the Software and App Development competencies. In fact, the difference between the distributions is highly statistically significant (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p = 0.00000009 and 0.00000002). The difference suggests a gap in graduates’ preparation in the knowledge and skills needed to be makers, rather than just users, of geospatial technologies. That’s troubling.

Finally, we invited respondents to offer advice to the GIS education community. 143 of our 226 (62%) respondents offered advice. The most common advice (41 comments) was to challenge students to code, to build models and apps, and to use up-to-date technologies.

“Make GIS harder.” One wrote. "Include more data science. More machine learning. More computer science. Programming ability should be heavily taught from day 1. Every class should use programming.”

Another advised, “Coding is such an important aspect of advanced geospatial analysis that it should be addressed in even basic classes.”

“The most important thing I wish I had learned as part of my undergrad GIS curriculum is basic programming/scripting, particularly with python and SQL,” another respondent observed.

Said another, “Define a curriculum that maintains the importance of Geography, yet incorporates GIS, scripting languages, and web development early and often in coursework.”

Thirty more respondents encouraged educators to create more realistic-as in applied and up-to-date- learning experiences for students.

“Make sure your students have a dose of the real-world before graduating.”

“They're going to need to approach things from a non-GIS point of view. Find out what people are trying to accomplish and then talk with them about what GIS can deliver.”

“Get on the cutting edge more. Most classes are outdated”

“Design a course or degree like it's a real job from class 1. … GIS is not the normal way of doing things so neither should the study of it.”

So, what does Esri’s Education Outreach team conclude from these findings, and what do we advise? We recognize that curriculum design is a zero-sum game. New educational objectives and content can only be added to courses and certificate and degree programs at the expense of other objectives and content. And many educators have discovered that less rather that more content, and fewer rather than more objectives, often lead to better learning.

Still, we aim to help leading academic programs that seek to retool their curricula and infrastructure to align better with the trajectory of evolving GIS technology and professional practices. To that end, we’re establishing a “GIS Education Modernization” program that will:

· Modernize education licensing to dispel real and perceived obstacles to adoption of more components of the ArcGIS platform, including ArcGIS Online, ArcGIS Pro, ArcGIS Enterprise, Insights for ArcGIS, and other related apps.

· Add technical depth to our outreach team to better support educators who wish to engage students more deeply in coding, app building and IT-related experiences.

· Provide concentrated outreach to the IS/MIS discipline to engage young scholars at the intersection of business and IT in the “Science of Where.”

· Develop and promote modernized “straw man” curricula and other best practices through a monthly webinar program.

· Expand and strengthen communication channels connecting our team with the GIS education community.

Our ultimate goal is to help willing education partners who wish to ensure that graduates enter the workforce with some level of competence in all three of the GTCM sectors: Positioning and Data Acquisition, Analysis and Modeling, and Software and App Development. Graduates are telling us, loud and clear, that two out of three is not good enough.

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.

-

Administration

38 -

Announcements

44 -

Career & Tech Ed

1 -

Curriculum-Learning Resources

178 -

Education Facilities

24 -

Events

47 -

GeoInquiries

1 -

Higher Education

518 -

Informal Education

265 -

Licensing Best Practices

46 -

National Geographic MapMaker

10 -

Pedagogy and Education Theory

187 -

Schools (K - 12)

282 -

Schools (K-12)

184 -

Spatial data

24 -

STEM

3 -

Students - Higher Education

231 -

Students - K-12 Schools

85 -

Success Stories

22 -

TeacherDesk

1 -

Tech Tips

83

- « Previous

- Next »