- Home

- :

- All Communities

- :

- User Groups

- :

- Conservation GIS

- :

- Documents

- :

- Noelia Laura Volpe, Argentina

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

Noelia Laura Volpe, Argentina

Noelia Laura Volpe, Argentina

Noelia L. Volpe PhD student, Conservation Bio Lab - Litoral Center for Applied Ecology (CECOAL), ARGENTINA

<-pdf 2018 SCGIS Conference Presentation mp4->

<-pdf 2018 SCGIS Conference Presentation mp4->

“Learning how to navigate in the wild: home range establishment by reintroduced red and green macaws (Ara chloropterus) in the Iberá Wetlands, Argentina" "The red and green macaw, Ara chloropterus, became extinct from Argentina in the 19th century. In order to restore its ecological role as consumer and disperser of large fruits and seeds a project was developed to reintroduce this species in the Iberá Wetlands, northeast Argentina.

<- 2018 Noelia Introduction on

<- 2018 Noelia Introduction on  her work with the Red & Green Macaw in Argentina

her work with the Red & Green Macaw in Argentina

2018 Scholarship Program Storymap -->

on historical Red & Green Macaw reintroduction sites in Northwestern Argentina

Noelia L. Volpe

PhD student, Conservation Bio Lab - Litoral Center for Applied Ecology (CECOAL), ARGENTINA

Ruta Prov. N°5, km 2,5 (3400) Corrientes, Argentina

Institution email: info@cecoal-conicet.gov.ar

Institution website: www.cecoal-conicet.gob.ar

(Scgis Years: yr18 )

Skype: noelia.volpe

email: noelia.l.volpe@gmail.comnoelia.l.volpe@gmail.com

I am a PhD student working on the reintroduction project of the red and green macaw (Ara chloropterus) in the Iberá Wetlands in Argentina, where it became extinct during the 1800s. This is a joint project between a government-funded research institution (CECOAL) and a conservation NGO (CLT). My thesis will focus on analyzing different aspects that influence the success of a reintroduction. For this, I will need to run habitat distribution models, map changes in food availability in space and time and identify space use patterns of the released individuals. This is a unique project, as it is the first time someone attempts a macaw reintroduction in a fragmented landscape where there are no wild counterparts that can serve as an example for the released individuals, and thus require and intensive behavioral rehabilitation process. It is quite challenging from the GIS point of view both for the logistics of gathering the GPS locations of the birds but also for the complexity of the models I am planning to run, which will include both spatial and temporal data.

I have been living in an isolated rural area for two years now and have been out of touch with the advances in the GIS world (I am still working with ArcGIS 10.1!), as well as have seen my GIS-related skills diminish. This year I will finish with the data collection for my PhD and leave the field site in order to start processing my data; I need to be ready to face the spatial analysis that lies in front of me. I look forward to the training provided by the SCGIS program to sharpen my skills again, gain new knowledge, get me up to date with the latest GIS tools and help me resolve the problems that will inevitably arise when I start to analyze my data. I am very excited about the fact that the program will have a strong emphasis on students’ individual projects, as it is usually very hard to find a course that allows tackling specific problems rather than overall concepts. This is particularly true for GIS in Argentina, where courses are taught only sporadically and aimed at beginners, with little to gain by people with advanced knowledge on the topic.

I think it is important to attend to conferences and training in person, rather than relying on long-distance interactions. When we are looking for people or knowledge online, we do so biased by where we think the answers will be. This leaves us with a narrow scope of solutions for our problems. In a conference, specially one as large as this one, we get to meet people working outside the spheres of what we are used to, making us face new ideas and concepts. Being exposed this multiplicity of topics might help us find that solution we were looking for in places we weren´t looking at. Participating in this program will not only help to improve my knowledge but also get me back into the GIS scene. In this stage of my career I´m advocated to being a field biologist, but I see myself dedicating myself to conservation GIS once I settle down into a life that doesn´t require so much time out in the field. Networking in a conference such as this can help me find the right people that will help me advance towards the direction I am looking for.

Once I get back to Argentina, I plan to get more involved in the SCGIS chapter by increasing my participation in forums and, if possible, organizing workshops to share my knowledge. I see a career in Conservation GIS as part of my future, as I truly enjoy working with spatial data, designing maps and using my programming skills to create tools to analyze data.

- Organization's work: I am part of the Conservation Biology lab of the Litoral Center for Applied Ecology (CECOAL), a government-funded research center that studies diverse aspects of the regional ecosystems in the North East of Argentina, ranging from genetics and ecology to paleontology and hydrology. The institution, funded in 1973, is moving towards a more active role in promoting the sustainable use of natural resources. This is done by investing in the development of ecological research to develop management policies to protect the environment and recover degraded ecosystems, as well as counseling for development programs that involve the modification of natural areas in order to prevent or reduce its negative effects.

The work of the Conservation Biology lab, led by Dr. Adrian Di Giacomo, focuses on studying the evolution and biology of target species of conservation interest in the North East of Argentina. It involves not only the production of base knowledge necessary to understand the best ways to manage wild populations and their habitats but also the study and development of conservation techniques. These include, for example, the active management of the endangered Saffron-cowled blackbird (Xanthopsar flavus) to increase its reproductive success and the reintroduction of the locally extinct red and green macaw (Ara chloropterus). The lab interacts with other institutions, both at the government and private level, to transfer the knowledge it generates so it can be applied to the development of management policies, the design of protected areas and studies of environmental impact.

I also work in close relationship with The Conservation Land Trust (CLT), an NGO whose goal is to contribute towards promoting a healthy Earth through the creation of protected areas. CLT operates by buying land, restoring it ecologically through the reintroduction of extinct fauna and eradication of invasive species, and donating it to local governments for the creation of national parks. In addition, it works with local communities to promote the development of economies that will contribute to sustain the ecosystem, such as ecotourism. In Argentina, its main work takes place in the Iberá Wetlands, within the province of Corrientes. Iberá is one of the planet’s great freshwater wetlands, covering more than 1.3 million hectares of grasslands, marshes and forests in northeastern Argentina. The Iberá region experienced one of the worst defaunation processes in Argentina during the 20th century. Through subsistence and commercial hunting, competition with cattle ranching and deforestation, species such as giant anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), collared peccaries (Peccary tajacu), tapirs (Tapirus terrestris), red and green macaws (Ara chloropterus), jaguars (Panthera onca) and giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) became extinct in the whole province. Other species such as the pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus), maned wolf (Crisozyion brachiurus), marsh deer (Blastoceros dichotomus) and cougar (Puma concolor) became very scarce in the region.

In 1983, Iberá was declared a 1,300,000 ha nature reserve, a portion of which became a Provincial Park in 2009. In 2016, the Iberá National Park was created, when CLT donated 23,000 ha to the National Park Service. 117,000 ha more will be donated in the next 3 years, adding up to 140,000 ha of National Park, adjacent to the 550,000 ha already existing Iberá Provincial Park. These protection measures enabled the slow recovery of the region’s wildlife, including what are nowadays abundant populations of caimans (Caiman latirostris and C. yacare), marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus), brocket deer (Mazama gouazoubira) and capybara (Hydrochoierus hydrochiaeris).

In 2007, CLT began the Iberá Rewilding Program that aimed at re-establishing sustainable populations of all locally extirpated fauna, looking towards restoring the ecosystem rather than the recovery of individual endangered species. Since then, they have successfully reintroduced one locally extinct species (giant anteater), created two stable populations of an endangered one (pampas’ deer) and began the reintroduction process of four more mammals (tapir, collared peccary, and jaguar) and one bird: the red and green macaw.

The red and green macaw reintroduction project began on 2014 as co-joint work between CECOAL and CLT as an effort to bring back a species that is extinct in Argentina. The red and green macaw used to inhabit much of the north of Argentina but habitat destruction and persecution for their feathers, meat and the pet-trade led to its extinction from the province of Corrientes in the 1800s and from the country itself in the 1900s. This, together with the disappearance of other large-bodied frugivores such as the tapir, peccary, bare-faced curassow (Crax fasciolata) and glaucuous macaw (Anodorhynchus glaucus), the latter extinct worldwide, meant the disappearance of large-seed dispersers from the ecosystem. The absence of this ecological role can have a significant effect on slowing the rate of recovery of forest patches such as the ones found in the north of the Iberá wetlands, which have become degraded due to human action (e.g. selective logging). The reintroduction project aims to begin the process of restoring this missing ecological role by establishing a founding population of red and green macaws, which will act as a source of individuals to colonize the rest of the system.

The project consists of three stages. First, birds donated from different zoos are taken to a rehabilitation center in the capital of the province (Corrientes), where they undergo a quarantine period. Second, they are taken to a pre-release cage located deep inside the wetlands, where the birds get used to their new environment. Finally, the macaws, wearing Holohil AI-2C collars, are released into the wild and a monitoring period begins. During the first months after release, food supplements are provided in order to make sure the birds are receiving the nutrients they need. As the macaws learn to find their own food resources, the supplementation will be gradually reduced until it stops completely and the macaws become completely independent.

I began working at the Conservation Biology lab on my PhD in early 2016, when the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) awarded me with a scholarship. My relationship with the lab started much earlier though, on 2014, when I began to collaborate in the Red and Green Macaw Reintroduction project first as a GIS technician and later as the field biologist in charge of the macaws during the pre-release stage. Nowadays I am in charge of monitoring the released birds, looking at their movement and activity patterns. Using telemetry equipment, I follow the birds daily, recording their position and activities, as well as the locations of the trees were they forage. I also collect data on food availability by monitoring the reproductive status of select fruit-bearing species that can be potential food sources for the macaws and surveying forest patches in order to understand the abundance of these species.

My thesis focusses on analyzing different aspects of a reintroduction project that can affect its outcome and it involves several spatial components. On one hand, I will look at the space use patterns of the released macaws, analyzing the expansion of their home range, establishment of activity core areas and use of food resources. On the other hand, I will model their potential distribution by generating maps of habitat availability. For this, I will run occupancy models to predict the distribution of the tree species they use as food resources and combine that information with forest patch characteristics (size, distance to populated areas, and time since human occupation, among others) in a multi-criteria model. As different species are producing fruits at different times of the year, I will produce maps that reflect changes in food availability month to month.

The maps I generate using these models will allow me to identify the areas that might be colonized by the macaws. This will help me identify regions of potential conflict with humans and take proper action (talking with neighbors, educational campaigns) before these arise.

- History: Since a young age, I have been interested in studying wildlife; that is why as soon as I left high school I enrolled to obtain a BS in Zoology. During my first year of college, I discovered the existence of bird field guides, and became an enthusiastic birdwatcher, naturally leaning towards research in ornithology. This led me to volunteer for a project studying Magellanic Penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus), do an internship working with the endangered Strange-tailed tyrant (Alectrurus risora) and apply for a research grant to study nest-site preferences of Monk Parakeets (Neotropical Ornithology 22: 111-119, 2011). In 2009, I participated in the workshop “Ecology and Conservation of Birds”, an intensive ten-day course held in the rainforests of the north of Argentina. This was a deciding point in my professional development as it made me aware of the issues of habitat fragmentation and the implementation of forested corridors to increase animal movement. This got me to read more about this topic and eventually decide to work on landscape ecology.

For this, I applied to a Fulbright scholarship, which allowed me to attend Oregon State University and obtain a Master’s degree on Wildlife Science. Before moving to the US, I decided to take a GIS course to improve my skills and be better prepared to face new challenges. This course was particularly important, as my new knowledge got me a job in Aves Argentinas, the main ornithological society of Argentina. My knowledge coming out of the course was very basic, as it only covered ArcView 3.3, but through trial and error I was able to teach myself to master skills such as using extensions (including Xtools, ArcView Projection Utility, KML to SHP, Shape Warp, Edit Tools and Demographics Analyst) and geo-referencing Google Earth Images. I used my abilities to map the location of lakes used by the Hooded Greebe (Podiceps gallardoi), a critically endangered endemic bird of Argentina (Bird Conservation International. 22: 383–388, 2012), and identify the space use patterns of multiple Neotropical migrants.

My master’s thesis at Oregon State University (OSU) consisted on studying how forest fragmentation affects movement patterns of the Green Hermit hummingbird (Phaethornis guy) in an agricultural landscape in Costa Rica (Ecological Applications. 24:2122–2131, 2014). Knowing my analysis would focus on spatial data, I took several GIS-related courses, becoming more aware of the power of visual representations to convey information on spatial data. When I realized the complexity of what I was trying to analyze, I decided to learn how to program in Python in order to be able to run my analyses in multiple computers. This is when I fell in love with GIS; I loved the challenge of finding and combining the right tools to get where you want, as well as creating my own and sharing them with the world to make other researcher’s work easier.

After I returned to Argentina I began looking for a way to combine my academic knowledge with conservation actions with direct impact on the ecosystem, which led me to join the Red and Green Macaw Reintroduction project in 2015.

- Local SCGIS work: I joined the SCGIS chapter on 2015, after learning about it from Carlos De Angelo, whom I met during a GIS workshop he was teaching. My connection with the chapter is through participation in forums, though sadly not as much I would like to given my isolated living situation. I really enjoy sharing knowledge with other people. Given I self-taught myself many of my skills and know the hardships associated to doing so, I want to help ease the way of others that might be struggling with issues I’ve already faced, ranging from simple tips on how to better navigate an excel spreadsheet to more complex tasks such as writing computer programming codes to simplify tasks

- What is the most unique and the most challenging about the conservation/GIS work that you do?

The Red and Green Macaw reintroduction project is unique for trying to bring back to Argentina a species that had become extinct from the country. The absence of a source of wild individuals to conduct translocations means that we have to rely on donations of captive-bred birds, which have often not developed the skills needed to survive in the wild (e.g.: resource gathering). In contrast with other reintroduction projects in which the released birds can learn these skills from wild counterparts, be it from the same or related species, here we have to face the challenge of having to teach them ourselves. Thus, the macaws in the project undergo a behavioral-rehabilitation process that focuses on three aspects: predator avoidance, flight training and wild-fruit recognition. Predator avoidance conditioning includes the use of a trained cat and a falcon, which simulate an attack to an embalmed macaw near the birds that will be released while playing macaws warning calls. Flight training involves the use of automatic food dispensers located on both extremes of a 25m long flight cage, which delivers food combined with a bip sound to promote flight from one extreme of the cage to the other. Wild-fruit recognition involves presenting the macaws branches with fruits available in the surrounding areas, so they will be able to identify them as well as learn how to move on unstable surfaces. We also train the macaws to respond to a whistle with which we guide them to feeding platforms distributed in different forest patches, in order to promote exploration and the gradual expansion of their home range.

From the GIS perspective, there are different types of challenges. On one hand, there is the challenge of gathering GPS locations of the released individuals. GPS tracking technology is not available for this species yet, as the macaws tend to destroy any device attached to them using their strong bills, The only tracking system that has worked this far are VHF collars. The detection range for these, using a hand-held antenna, is of only 3km. This is a very short extent for animals such as macaws, which can cover long distances in really short time, making them very hard to follow. Another aspect that complicates obtaining good location points is the landscape structure. The area consists of isolated forest patches surrounded by flooded terrain, which is particularly hard to go though (e.g.: tracking the macaws often involve walking with water up to the waist). All of this means I will have a lot of missing data regarding the real space use of the macaws, as I will not always be able to find them at a forest patch before they move away from it.

Another challenging aspect from the GIS standpoint is data analysis, as I have to work not only with spatial but also with temporal data. This means I have to be able to identify patterns in both space and time as well as deal with temporal autocorrelation in addition to spatial autocorrelation. I consider my main GIS challenge will be to model fruit availability throughout the year, as for this I have to integrate occupation models, which will allow me to identify the potential distribution in space of trees, together with information on the presence of fruits throughout the year for each target species. An issue that will further complicate running these models is the fact that the regional satellite images I have access to (Bing, Google Earth) are of variable (mostly bad) quality and usually outdated, which will make difficult to extract good information from them.

Plan for the next year:

I will finish collecting the data needed to run my models within the expected expansion area of the incipient macaw populations (i.e.: visit 50 forest patches within a 50km radius buffer around the release point). The skills gained during the SCGIS program will help me create maps of regional and seasonal fruit availability with which to predict macaw movements. A critical moment in the reintroduction process is the first days following the release, as there is a great risk of the individuals flying far away from the release site and not knowing how to come back due to their lack of knowledge of the terrain. It is important for recently reintroduced macaws to stay near the release site so we can monitor their health and provide food supplements while they learn to forage on their own. We have seen that the likelihood of the birds leaving the area decreases if they find food in the immediate surrounding of the cage. Knowing at which times of the year there is low food availability around the release area will help us know when we need to increase the amount of food supplements we provide, in order to reduce the chances the macaws will fly away due to hunger. Knowing where to expect to find food sources at a larger scale will also help us look for individuals that go outside our detection range. In addition, predicting where we are more likely to find the macaws at a given moment of the year will help us prevent potential conflicts such as the ones that might arise if the macaws fly outside the national park. We can identify risk areas where there is an increased likelihood of encounters with humans and take measures to prevent negative outcomes of such interactions (e.g. talk with neighbors; organize workshops).

Outside of the macaw reintroduction project, CLT will use the habitat models to evaluate the possibility of reintroducing other frugivorous species in the area in order to continue its mission of ecological restoration. The habitat distribution maps will also be shared with the National Parks Administration, for them to use as a way to assess the conservation status of the forests inside the Iberá National Park, identifying locations that might be in need of restoration actions. The local park ranger has also asked me for help to create a map showing the distribution of the different biomes present within the national park, information which is not currently available as the park was only created recently (November 2016). This far I have not been able to do so due to my lack of skills analyzing satellite images. The knowledge I gain under the SCGIS scholarship will allow me to provide him these maps, which will greatly help in the management of the protected area.

- GIS work: I am currently self-taught, but I have attended a fair amount of courses in the past few years. My first approach to GIS was during a beginners’ course in Argentina, where I learnt how to use ArcView 3.3. While studying at Oregon State University for my Master´s degree (2011-2014) I took two GIS courses taught by Dr. Jim Graham: “Geographic Information Systems and Science” and “GIS Programming in Python”. Through them, I learnt both how to use ArcGIS (9.x through 10.1) and Python programming (using the WingIDE interface). I also took two GIS-related courses by Dr. Julia Jones, “Spatio-temporal analysis in ecology and earth science” and “Spatial Statistics”, through which I learnt about spatial and temporal autocorrelation and the basics on how to approach its analysis using ESRI’s statistical tools. Finally, in 2015 I attended a course in Argentina taught by two SCGIS past scholars: Carlos De Angelo and Cristian Schneider. During this course, I learnt to classify raster data and the basic theory on how to run multi-criteria models. Since then, my GIS learning has been self-taught through trial and error and using online forums.

Your GIS Work: The GIS project I would be working on during the SCGIS program will consist on mapping habitat availability along the year for the species I am working with, the red and green macaw. The landscape at my field site consists in forest patches of variable size surrounded by flooded terrain and grassland. Thus, “available habitat” will be a subset of the existing forest patches that has the adequate characteristics as defined by a habitat suitability model. To build this model I will need to be able to characterize the forest patches using information obtained from satellite images, which I currently do not know how to do. In particular, I would like to know if there is a way to identify flooded areas, as I think these affect the type of vegetation inside a forest patch. I will also need to learn how to turn information from vector data to raster, such as distance to closest human settlement, presence of cattle and patch size. The models will have a temporal component, given by information I have been collecting on the reproductive status of multiple fruit-bearing tree species along the year. I will have to “turn on/off” certain species on different months depending on whether they are fruiting or not. I will not have “presence-absence” data on the distribution of these tree species in the landscape, but the probability of their presence in a given forest patch as determined by an occupancy model. Thus, I will have to find a way to map these probabilities in space (and time) in order to represent the distribution of food resources, which I then have to include in the habitat suitability model.

http://datadryad.org/resource/doi:10.5061/dryad.27900

This is the link to the script I wrote to analyze the data for my Master’s thesis. It extracts the data required to run a Step Selection Function, which analyzes which characteristics of the environment might be affecting an individual’s decision to move in a given direction.

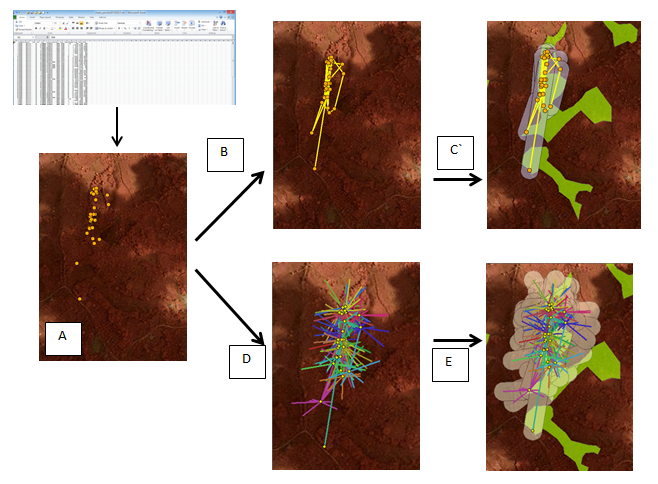

Among other things, the code:

- Turns excel data into location points (A)

- Generate shapefiles of step lines connecting consecutive points (B)

- Generate buffer around lines and estimate proportion of forest within them (C)

- Generate steps in random directions around each location point (D)

- Calculate proportion of forest around random steps (E)

2018 Paper Title & Abstract: Learning how to navigate in the wild: home range establishment by reintroduced red and green macaws (Ara chloropterus) in the Iberá Wetlands, Argentina

Introduction: The red and green macaw, Ara chloropterus, became extinct from Argentina in the 19th century. In order to restore its ecological role as consumer and disperser of large fruits and seeds a project was developed to reintroduce this species in the Iberá Wetlands, northeast Argentina. The current paper analyses the first stages of the reintroduction process from a spatial point of view, looking at the changes in space use across time since the release of the macaws.

Methods: On June 2017 a group of 7 individuals was released into the wild inside the Iberá National Park. This group included 3 couples and a single female. Food supplements were offered daily to ensure adequate nutritional levels. VHF collars were attached to the birds and used to monitor their activities and movement patterns. The birds were followed by foot, regularly recording their location/activity points. This information was used to generate utilization distribution (UD) maps from which home range polygons were constructed. A home range was defined as the area within the 95% isopleth of the UD, while core areas were defined as the area within the 50% isopleth of the UD. The information on activity patterns allowed to identify activity centers, which included feeding and resting grounds and, for one couple, breeding grounds.

Results: All individuals showed a large increase in their home range size since their release, except for one couple which stayed almost exclusively in the area around the pre-release cage. The main feeding grounds of the rest of the macaws were outside the National Park. All the birds used the vicinity of the pre-release cage as the rest area. One of the couples lived for over a month at a distance of 8km from the cage, feeding exclusively from wild fruits, though it later re-established itself near the release site. One female moved outside detection range 6 months after being released and was not found again.

Discussion: All the birds were able to survive for at least 6 months after their release, locating their own food resources and expanding their sphere of action. These preliminary results would be evidence that reintroduction seems to be a viable conservation tool for the species. The fact that the birds have to travel long distances to find the trees they need is an indicator of the degraded state of the forest patches inside the reserve. This information can be useful for the authorities of the National Parks Administration, as it can be the base to begin developing forest-restoration projects.

xEndangered xSpecies xBird xHabitat xReintroduction x2018Scholar x2018Talk xScholar xTalk xWomen xLatinx xArgentina xLatinAmerica